Make It Playful

An Essay by Rachel Moore

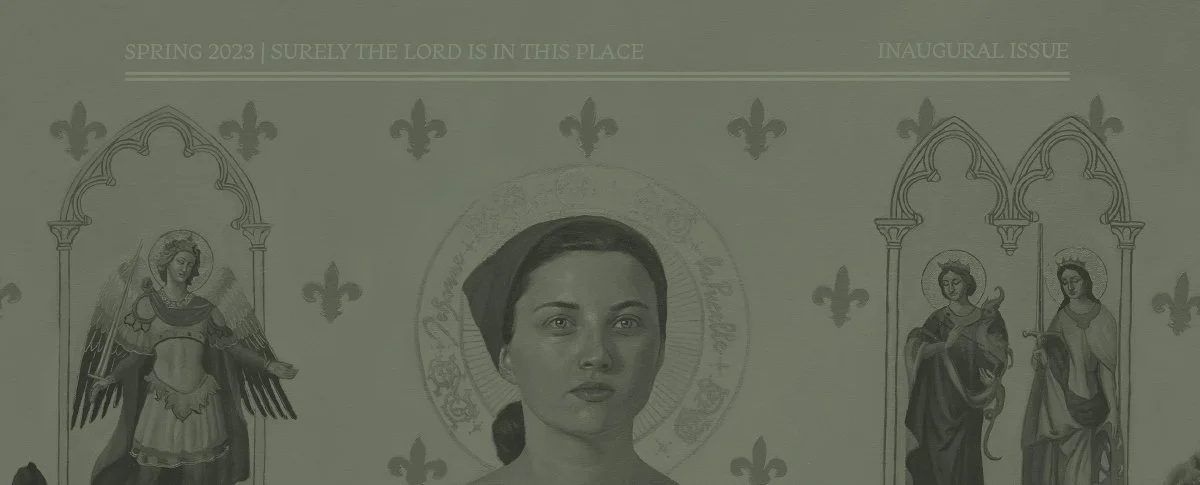

“Just play around with it,” Manny reassures me, zigzagging the cursor across a blank page on the computer screen. It’s Saturday morning, and I’m visiting the home studio of sacred artist Blair Piras and her husband Manny to brainstorm design ideas for Joie de Vivre, the print journal published by The St. Louis IX Art Society. The three of us huddle before the monitor where Manny, with heroic patience, gives me and Blair a crash course in Adobe InDesign to get the journal’s layout started. Off-screen, Blair doodles a bouquet of irises while nodding along to Manny’s pedagogy. I pick at a croissant and try to deflect the thought of how overwhelmed I am by having to meet the project’s deadline while learning a software entirely unfamiliar to me. My gaze then drifts to the corner of the room where morning sunlight flutters over a massive oil painting of the Woman Clothed with the Sun resting on Blair’s easel, that sacred platform where she’s created so many faith-inspiring works commissioned by local parishes and even by the Word on Fire Institute. And somehow more striking is the Fisher Price easel beside Blair’s where her toddler Auguste babbles to himself and, in imitation of his mother, traces his crayons across a sheet of construction paper. I then realize I’m sitting in what’s more than just an art studio. It’s a playroom. All of the faith-inspiring, transcendent images Blair has painted come from, of all places, her son’s playroom. This sacred space to play is the birthplace of beauty.

Young mammals of essentially all species play. We Homo sapiens are the mammals with the most to learn, and therefore we require the most play. Can you imagine that without play, the very survival of the species would be at stake? Through physical play, we develop fit bodies. Through group play, we develop social and emotional skills. Through risky play, we learn to experience fear and grow in the virtues of courage and perseverance. Thus children become more human when they play, making sense of reality through the images stored in their moral imaginations and discovering their own identities through imitation of their guardians and mentors.

So too do Christians become more Christian when we play. Play is pivotal in holistic Christian formation just as prayer, performance, and proclamation are. The liturgical life, the tradition of Catholic art and literature, sacramentals, the rhythms of sabbath and work, dance—all of these examples of play give expression to our baptismal identity as disciples of Christ. When we “babble” the Mysteries of the Rosary, we become immersed in the narrative of Christ’s life on Earth and are joined more intimately with him through scriptural images. To play well, then, is to pray well. We are therefore called to approach our ecclesial expressions of play with the same joy and reverence the child Auguste has when approaching the Crayola masterpiece on his Fisher Price easel. Blair creates, and Auguste plays along to echo the gifts of his mother. God creates, and we play along to echo the goodness of God, the Giver of all gifts.

In The Spirit of the Liturgy, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger proposes that to better understand liturgical living, we’ve got to think in terms of play: “Play, though it has meaning, does not have a purpose…for this very reason there is something healing, even liberating, about it. Play takes us out of the world of daily goals and their pressures and into a sphere free of purpose and achievement, releasing us for a time from all the burdens of our daily world of work. Play is a kind of other world, an oasis of freedom, where for a moment we can let life flow freely.” But what sets apart play in liturgical life is that it’s not make-believe; just the opposite, it’s realer than real. When we go to Mass, we do not put on costumes as children do when they play dress-up. We go as ourselves, and we are sent forth from the liturgy as more of ourselves and more conformed to the Body of Christ through the celebration of Eucharist.

Play is not productive; even better, it’s fruitful. What comes of play is a bounty of wonder and receptivity we experience in no other way. According to philosopher Josef Pieper, play as a branch of leisure “cannot be accomplished except with an attitude of receptive openness and attentive silence—which, indeed, is the exact opposite of the worker’s attitude marked by concentrated exertion.” Play thus is an activity meaningful in itself. It conditions us to become like the contemplative Mary in a crowd of the bustling Marthas we over-glorify in this busy century. When we dispose ourselves to be liberated by ecclesial play, we dispose ourselves to be liberated by Christ. We are loosened from the yoke of having-to-be-productive, and instead we make space for the Lord to be productive within us. Competition for dispensable daily bread is redeemed into devotion for the ultimate and perfect Living Bread.

As counterintuitive as it sounds, play, like work, demands discipline. Games have rules to follow, some silly, some solemn. And cheating those rules spoils the fun. So, practice discipline accordingly when you incorporate play into your Rule of Life. In his book Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide, Monty Python’s John Cleese describes how the most fruitful and creative of thinkers are the ones who intentionally carve out time in their daily routines for uninterrupted play—no exception! The best of Christians do the same as they drop everything to follow the Commandment to keep the sabbath holy and free of tedious work. What makes the Lord’s Day holy is worship, leisure, and play, and all must be uninterrupted. This means getting your shopping done the day before, closing out the computer tabs, and waiting to answer those emails tomorrow when the work week begins again. You’re free from work for one day, so make the most of it and spend your time absorbed in the sacred and the playful. It’s this playful spirit we carry into the rest of our work that makes the week not only bearable, but also fruitful.

Manny’s artist-to-artist advice to “just play around with it” is a rule of the game as relevant to Christian formation as it is to creating good and beautiful artwork. Like Blair’s son Auguste, you’ve got to play and find yourself doing something while not exactly knowing what it is you’re doing. Sometimes it’s not your business to know. Your business is to let the play happen, to let the play liberate you and transform you back into a wonderstruck child. The Lord looks at our work and our play with the same affection Blair feels in looking at the crayon scribbles upon Auguste’s easel. The beauty comes from the babbling, from the scribbling, from the clumsy hands of children working with all the grace they can get.

Good art isn’t manufactured tidily. It’s played around with. Any artist has enough discarded sketches, any novelist enough drafts consigned to the trash can, to prove it. But good art has to be played around with, and so do we, as the words of Jeremiah 18 remind us: “This word came to Jeremiah from the Lord: Arise and go down to the potter’s house; there you will hear my word. I went down to the potter’s house and there he was, working at the wheel. Whenever the vessel of clay he was making turned out badly in his hand, he tried again, making another vessel of whatever sort he pleased. Then the word of the Lord came to me: Can I not do to you, house of Israel, as this potter has done?—oracle of the Lord. Indeed, like clay in the hand of the potter, so are you in my hand, house of Israel.”

Pray, and make it playful. Wear pink on Laetare Sunday. Giggle a little the next time the priest pelts you with holy water from the aspergillum. Sing hymns loudly, even if you stumble over the Latin pronunciation. And treat your family to beignets and a day on the playground after Mass. These are the saint-making moments.

Rachel Moore is an artist from St. Charles Parish.