Savior of Stories

An Essay by Rev. Clinton Sensat, STL

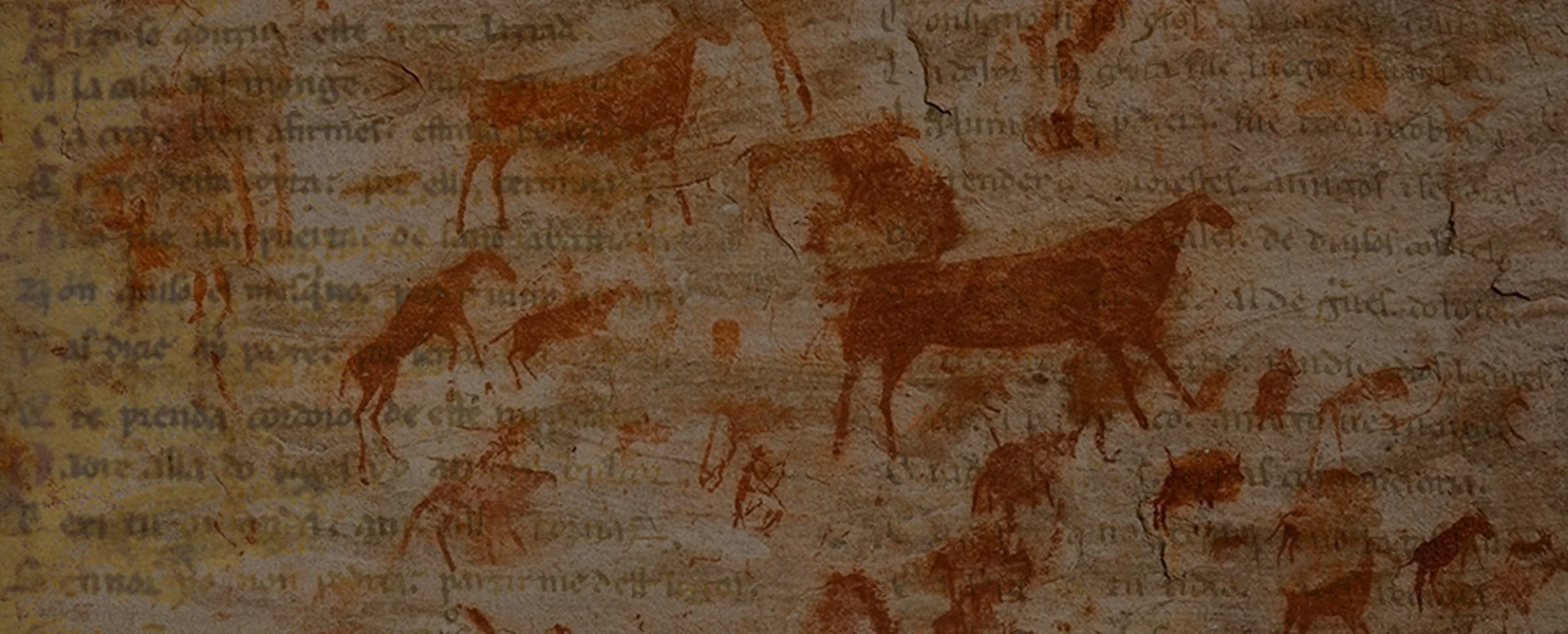

Picture this: the wind blows cold, and you sit within the cupped palms of a cave. People huddle round for warmth and wisdom. The hierarch tells of Horse, prancing through the field. He seizes ash and ocher and walks into the deep to summon Horse upon the living rock.

Now the wind blows hot, and you hear the trilling of cymbals and smell the fragrant balsam. You lounge upon silk in the Sultan’s court, and hear the tale of Scheherazade, who saved her life nightly by myth and magic. As Aladdin grasps the lamp, the story stops, and your heart hangs suspended for another sultry eve.

The wind blows ill, and a politician’s voice sounds from the screen. Calls for social responsibility, environmental awareness, and concern for the future drone despondent from his tongue. But underneath it all there is this appeal: we have faced great trials, and overwhelming odds, amidst grave danger, and overcome. Together, we can make a difference.

From before the beginning of history stories have surrounded us, inspired us, united us – and divided us. The human engine runs on narrative steam. God has willed it so. He guides stars by gravity, atoms by electromagnetism, animals by appetite, and humans by stories. It is part of his ordinary providence. It is also part of salvation. Of the Persons of the Trinity, it was the Word who became man – for humans live by words. God guides and saves humanity by stories.

These are bold claims. Let me start with the first: God guides humans by stories in his ordinary providence. To understand this, remember that people make stories, but stories also make people. Let me give an example. Sally is a young lady with a hard life. She lost her dad when she was five. Her brother got cancer six years later. Kids at school teased her. She endured. She almost flunked tenth grade, but she applied herself, studied hard, and pulled out hardscrabble Cs. Now it is senior year, and she did not make the first cut for cheerleader. What will she do? We know what she will do, because we know her story – but more importantly, so does she. She will tell herself that she is strong, that she has overcome greater difficulties, that she can do this. The story becomes real because the story has become her. Countless other things have happened in her life. If she had focused on them, she would have told a different story about herself, and become a different person. Sally is made strong by her story, just as others are made bitter by theirs.

This points to something profound about human thought. Influenced by Plato and the Enlightenment, we tend to think of education as the communication of abstract truths. The perfect mind is full of sanitized facts. But is that how humans learn? Why do students ask without end, “Is this important?” It is not mere crass consumerist pragmatism, as elitist literati like to think. It is because humans learn narratively long before we learn abstractly. Umberto Eco discusses how a revolution took place in artificial intelligence as programmers moved from teaching computers abstract definitions to telling them stories. After all, how do we learn about umbrellas? Are they central poles with radial spars that suspend waterproof material? Or are they something we grab when it is raining so as not to get wet? Definitions shape dictionaries, but stories shape us.

If anything, this is truer at the level of nations. The great Catholic philosopher of the Enlightenment, Giambattista Vico, explores this mystery in his New Science. His expressed goal is to explore the social nature of mankind, by which God guides humanity. Vico arrives at a startling conclusion: all law and society are ultimately founded on stories, the myths the poets have told through time. Shelley stated that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Vico would agree. By poets, though, Vico does not mean the word twisters of a later age, but primeval mythmakers and storytellers, the first to create names for intuited realities. In Greek, poiesis means creating, and Vico was always alive to etymology. Poets are creators of peoples. After all, Babel taught us that languages make nations, not nations languages (Gen. 11). Vico verbally sketches magnificent images of early man running through the woods, committing sin, and being terrified by thunder. From this early man arrived at the idea both of a heavenly Thunderer and a behavioral taboo. Taboos became ethics, and myths became law. Societies arrived at social structures and civil statutes from the retelling and complexifying of their stories.

That may seem stark and cynical. It might describe primitives, but never us. But think a bit: how often has the story of the American Revolution been retold to protect the Second Amendment? How often has the story of the Civil Rights Movement been retold to justify some new social activism? Even today our society arises from our stories. And Vico would nod, for that is how God moves mankind.

This is the reason God sent preachers instead of princes or potentates. He knew words move us more than money, law, or influence. But sometimes stories lead us astray. Who can forget twentieth century Germany, the thesis of original Aryanism, and the myth of the master race? A story thrust the world into war and nearly destroyed the Jewish people. If stories are so mighty, what can one do when stories go wrong?

In a golden passage, St. Hildegard says Christ “changed the tales of human deeds that are told and heard into better ones, by erasing what was useless and keeping what was useful.” She is clear that this goes beyond the Old Testament to include pagan myths. Christ’s teaching transformed both prophet and poet. He is the Savior of stories, and therefore the Light of the nations.

He also saved us by stories. Stories were part of his ministry. St. Albert the Great says Christ taught in three ways: speaking, teaching, and preaching. Preaching revealed mysteries to faith, and teaching shaped our intellect. But he “spoke” when he told stories, and his stories moved our hearts. Many who struggle with Jesus’ preaching and teaching nonetheless connect with the story of the Good Samaritan. Christ was a storyteller, and his stories are an instrument of salvation.

Maybe what is missing in modern evangelization is stories. The internet is rife with apologetics. Books sprout abstractions like fungus after rain. Homilies are sweet with aspartame vagaries. People remain unmoved, except to cover mouths while yawning. But tell a story, and everything changes. Whether it is a conversion story, a vocation story, a personal tragedy, or even the much-maligned hagiography, people love stories. We should learn from Christ. He shaped nations by stories. He ministered with stories. He sent into the world witnesses, not philosophers. We who serve Christ should serve stories to hungry ears. Christ saves us by stories, and Christ is the Savior of stories. In Him all stories may be saved.

Editor’s Note: This essay originally appeared in the Spring 2023 print edition of Joie de Vivre. To purchase this issue, click “Subscribe” above.

Rev. Clinton Sensat, STL, is a pastor of Our Lady of Lourdes in Erath, LA.

Thumbnail artwork - Sermon on The Mount by Károly Ferenczy