Fatherhood, Once Removed

An Essay by Danny Fitzpatrick

Peering into earliest memory, I am met with two images. The first: my father, my younger brother, myself, seated on a bridge, our legs dangling, kicking gently against the warm concrete; my father holds a fishing rod, and an orange cork floats on the surface of the brown water below, questioning its depths. The second: I am running across the polished floor of my maternal grandparents’ kitchen and into the dim cave of their living room and clambering into my grandfather’s lap.

I can date neither of these memories very precisely except to say that the second, which is probably the earlier, remains from the first thirty months of my life, after which period my grandfather was dead. He was in his 60s when a blood clot caught in his heart and dropped him like a stone.

My paternal grandfather, too, died of catastrophic heart failure. I have no memory of him. He died when my father, the fifth of eight children, was only eight years old. My father used to keep my grandfather’s pocket watch in a small, latched compartment in his desk drawer and I used to take it out at times and wind it and listen to its gentle tick.

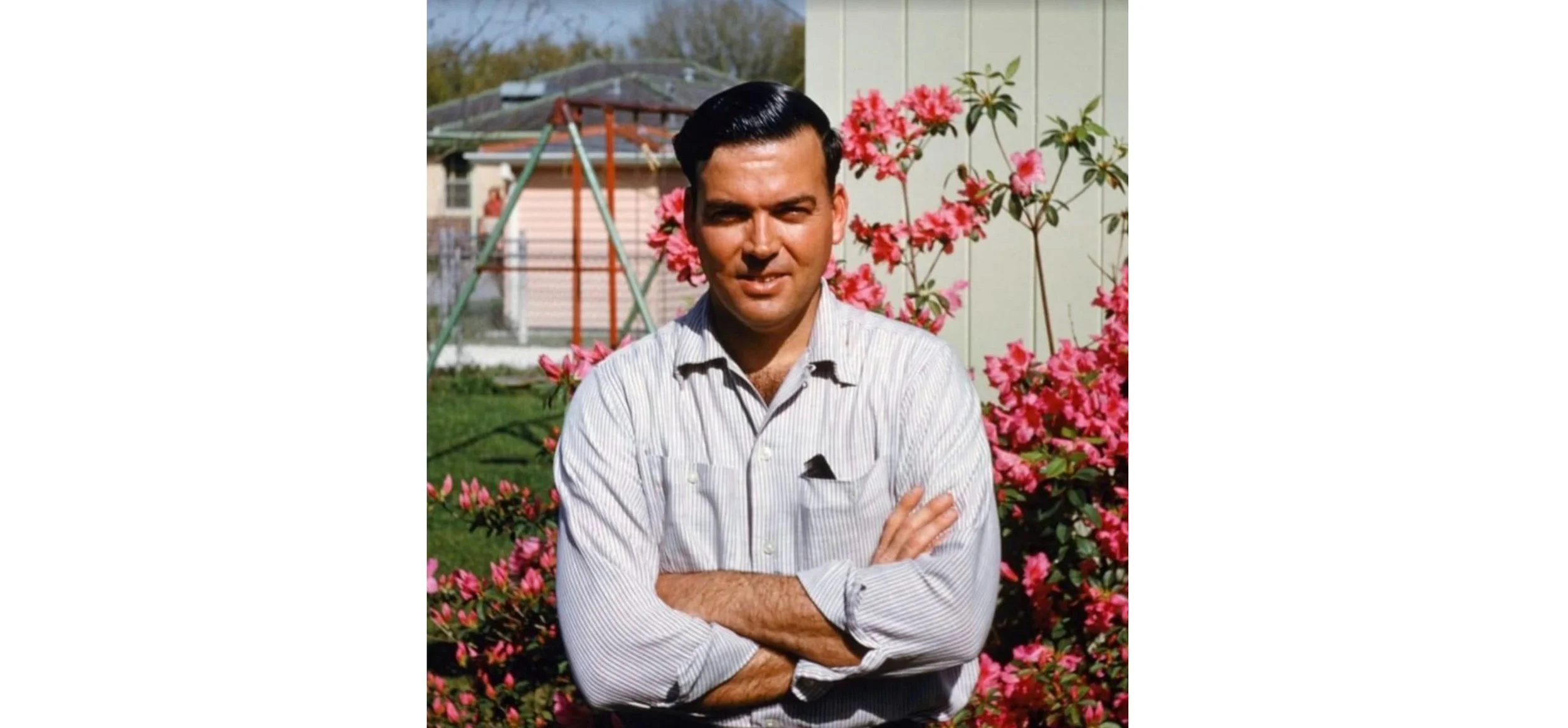

I was brought up in two large, raucous matriarchies in New Orleans, each delightful in its fashion, each marked by men most conspicuous by their retreat to memory, legend, and photograph. A tall man, pale, with lustrous black hair and a broad smile; a small Sicilian grinning out of a balding head creased with laughter, a French bulldog tucked under each arm.

I have thus been struck by a certain familiarity in two of Disney’s recent efforts, Coco and Encanto. Both the families Rivera and Madrigal are headed by formidable abuelas who oversee their children’s and grandchildren’s well-being with tenacity, to put it gently. Dead men loom over both families, exerting the ineluctable influence of their own myths—the one of unjust infamy, the other of unimpeachable heroism—from beyond the grave. Each absence leaves wounds which threaten to overwhelm the families.

While many have decried the cultural current seeping its woke way through Disney, the company continues to present us with a kind of family which is itself becoming the stuff of myth. Rare today is the family of shoemakers. Rare is the clan which gathers its several generations under the same roof, the same city, even the same state. Communal meals can hardly be had without the services of United Airlines, Amtrak, or the Greyhound. Fatherlessness abounds, not so much by death as by divorce, not so much by divorce as by apathy in the face of a materialist quest for eternal happiness. The broken family relationships of Coco and Encanto present something like paradise to the plight of countless homes across America.

The absent parent is nothing new to Disney, inasmuch as Disney has always managed to tell a good story. In Mufasa, the lion king, we see King Hamlet. In the Little Mermaid we feel the absence of Ariel’s mother just as we miss Miranda’s mother in the Tempest. We could say without too much exaggeration that the whole history of storytelling is indeed one of the absent parent. Telemachus sets out for word of Odysseus. Aeneas is frequently saved by the apparition of his mother, Aphrodite. Lear’s queen is dead. Orestes’ father, Agamemnon, is dead. Stephen Dedalus’ mother is dead. Shakespeare writes Hamlet in London; his wife and two surviving children are in Stratford. The Christ child must be in his Father’s house. And “they did not understand what he said to them” (Luke 2:50).

Then, too, a parent may be absent in his very presence. The greatest failures of King David are perhaps his failures as a father. Though he grows angry with Amnon over the rape of Tamar, he “would not antagonize…his high-spirited son; he loved him, because he was his first-born” (2 Sm. 13:21). Likewise, it is only when Absalom is dead that David calls him what he is: “my son.”

In Noah, too, we find a father far away from his sons. He has retreated, if only for a moment, into the absence-in-presence of the grape. Like Adam and Eve he has abused the fruit of the earth, and Ham has seen his father’s nakedness. Ham has not understood what it is to be a son.

Disney has in general stayed far clear of such biblical scandals. Indeed, in Coco and Encanto, it has admirably portrayed the sort of intergenerational family culture our world so desperately needs if it is to escape the diabolical atomization of man which is the hallmark of atheistic humanist democracies. Disney has even, as we have noted, pushed parental absence to the place where we expect it by nature; that is, in the grandparental generation. This may be a matter of delicacy. Once upon a time the absent parent was the stuff of fairy tale. Today the fairy tale is the unbroken family.

The power in the tale of the absent grandparent lies in that we do not so much need our parents to teach us how to be parents—our glands can manage much of that—as we need them to teach us how to be children, how to be sons and daughters.

That is, the primary relation at work in human life is not that of parent to child but rather that of God to creature, a relation which has been raised through covenantal filiation in order to incorporate us into the Sonship of Christ by making us partakers of his blood.

The dearest gift a father can give his children, and, in turn, his grandchildren, is not to become ever more the adept patriarch. It is rather to become more and more a son as he approaches the Father more and more closely. It is to approach death in the way an exponential curve approaches an asymptote, accelerating into the final beatific union the Father has made available to his children.

How often do we forget the Father and so forget our children? How often does a bottle or a smart phone or a business call or a deadline so dull our awareness of the Father’s love that we who are wicked fail even in that fatherhood Christ ascribes to us. When our children ask to play, do we hand them the excuse that we have work to do? When they ask for us to read a book, do we keep scrolling through our social media feeds? Do we know anymore how to give good things to them? If not, to what degree is it because we have forgotten our own Father’s love?

The love of a human father who understands that he is the Father’s son supplies a warmth and radiance wherein his family can bloom in its own Christian sonship. In Coco, for instance, Miguel, in possession of a fine musical talent, cannot develop his talent because music has fallen under his Abuelita’s interdict. Abuelita’s grandfather, Hector, is supposed to have abandoned the family in quest of musical fame. The family has, in the interim, managed quite well, yet they have cut themselves off from that music which expressed the joy of Hector, Mama Imelda, and Mama Coco’s love. Encountering his great-great-grandfather among the dead (we remember Aeneas descending into Elysium), Miguel learns at length that Hector had in fact turned away from music to return to his family, only to be poisoned by his partner, the great Ernesto de la Cruz. The latter, having stolen Hector’s future and risen to stratospheric fame, tries also to become a false father to Miguel. Only in learning the reality of Hector’s life can Miguel flourish, not simply by coming at last into his family’s musical legacy but by healing his family through a clear knowledge of the truth. Without such an encounter with the truth, which underwrites our own being, we cannot know ourselves. Fathers and grandfathers guide us above all by teaching us who we are. Absent that guidance, we fall prey all to easily to the crushing mechanistic weight of our age.

My father, I have said, was eight when his father died. As I approached my own eighth birthday, I became possessed of a certitude, never urgent, ever insistent, that my father would soon die. Surely his fate was my own. Never mind that I was the eldest surviving child while my father was the fifth of eight. Such are the syllogisms of childhood. Nonetheless, the year came and went, and I turned nine, and the past receded for a while. As I grew older and began to approach decisions of greater moment, I believe my father, though he has never said it in so many words, began to feel a need to give me that guidance which was never his. The results have varied, as they have since the days of Odysseus and Telemachus. Where my father’s success has been unqualified, however, is in his becoming more faithful—perhaps, in William James’s expression, more fit to live--as he has grown older. The Mass means ever more to him. I believe he has come to know Christ’s presence in the Eucharist more intimately. His words have grown fewer, his voice gentler, his concerns those of the Kingdom of God, a Kingdom whose Father is never absent. My father has become more and more a son, learning to stand beneath the Cross with Mary.

Our families will continue to fail unless we do the same, learning to be sons and daughters, learning that before our fathers, mothers, wives, and husbands could claim us, the Son was and is and ever shall be. Our sonship is not a matter in the first place of nature but of the grace which flows forth in water and blood, calling us into sacramental life, calling us to the Father who from before the foundation of the world would give us all good things.

Danny Fitzpatrick is the author of the novel Only the Lover Sings and editor of Joie de Vivre